The other day I saw a tweet that instantly made me want to check out a product:

Specifically, the part that says “getting random Kindle highlights each day.” That sounded awesome!

But what I found on the page he linked to confused me:

“Don’t let your Kindle highlights disappear.”

When I read that headline, I started thinking, Wait, do my highlights actually disappear after awhile? Is this some sort of highlight storage system?

At that point, I just wanted to find out how the product worked so I’d know whether I’d misunderstood the tweet that piqued my interest.

I opted in, went through the signup process, and quickly learned that it was a daily email digest that sent you things you’d highlighted in Kindle books (which is what I’d thought it was before I saw the headline).

Someone at the company shot me a friendly email asking for feedback on the product, so I explained how the signup page copy had confused me.

It instantly clicked. He completely agreed and pledged to incorporate the feedback on the next iteration of the page.

This reminded me of a question I’ve been thinking about for years now: Why does it always seem harder to write about our own products, especially when we’re launching them for the first time? And how can we make it easier on ourselves?

I’ve come up with 5 rules that I’ve found usually help.

(By the way, check out Rekindled! I’ve really enjoyed getting my Kindle highlights via email every day.)

1. Focus on being clear before being clever.

Notice the word “before” in that sentence. I call special attention to it because we copywriters have been guilty of perpetuating the myth that copy should always be clear instead of clever, no exceptions.

But this black-and-white mindset leaves out an important distinction—effective copy can be clever…as long as people can still clearly understand what you’re offering (and how it benefits them or solves a pain).

For example, remember that viral video that launched Dollar Shave Club? It was clever and ridiculous, but the product and offer itself were crystal clear: “For a dollar a month, we send high-quality razors right to your door.”

Nothing sexy. Just clear.

(That’s literally the third sentence in the video, by the way. Right after, “Hi, I’m Mike, founder of Dollar Shave Club dot com. What is Dollar Shave Club dot com?”)

It’s only after the value proposition is crystal clear that all the funny stuff that made the video go viral comes into play.

Lance Jones from Copyhackers wrote a great piece about the “clever vs. clear” fallacy a few years ago with an interesting split test that backs up their ability to coexist. ✌️

2. Remember the 3 ingredients of an effective value proposition.

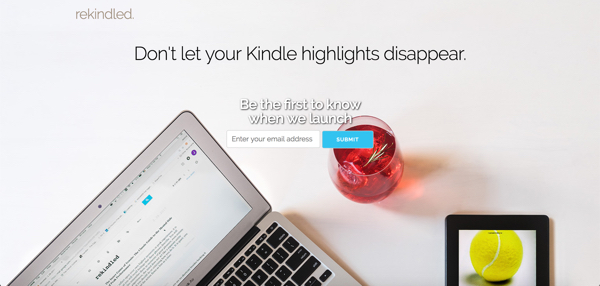

Writing an effective value proposition is deceptively difficult, and it doesn’t help that our favorite companies frequently bombard us with advertising with super unclear copy. For example:

Where’s the clarity? Do the rules not apply to Apple?

Actually, no—they don’t really. Apple has reached a stage of their business that 99.9% companies will never see. If your brand isn’t already iconic and loved by millions, you probably shouldn’t try to write about your products like Apple, even if you love their advertising.

That’s why I like the way Product Hunt advised makers to write about their products in their recent “How to Launch on Product Hunt” post (my own emphasis is added):

“Describe what your product does in under 60 characters. Be specific! Communicate the value your product provides to the people you’re trying to reach, even if that means leaving out 95% of the features. Avoid slogans, optimize for how users search for products after launch day.”

This isn’t just great advice for launching on Product Hunt—it’s great advice for anyone trying to attract early customers. Let’s break it down:

- “to the people you’re trying to reach”: Before thinking about the value or how to describe what your product is, think about who it’s perfect for. What kind of customers are you trying to reach right now? Pinpointing who you’re talking to makes it easier to figure out what to say and how to say it.

- “Communicate the value your product provides”: Once you have an idea of who you’re talking to, think about what they will get out of using your product.

List out the different types of value it will give them. Then list out the pains those values solve. Now think about which of those values and pains are most likely to immediately grab their attention. Which ones have the strongest emotional pull? And are you describing them the way your customers would? - “Avoid slogans, optimize for how users search for products”: Most of the time, slogans are more valuable for established businesses that have already done the hard work of attracting lots of customers and achieving some semblance of brand awareness. Take a look at what comes up when you do a Google image search for “slogan”:

For early businesses, it’s much more valuable for people to quickly and easily understand exactly what your product is and how it helps them. If your product is a calendar app, make sure you tell people it’s a calendar app, and not just some vague new way to stay organized.

The competition for attention is greater than ever, and if your brand hasn’t already established some equity with the audience you’re hoping will buy your stuff, it’s going to be even harder to cut through the noise.

Specificity usually makes for the sharpest knife.

3. Learn how people talk and think about the problems your product can solve.

Until sales start coming in, you can’t know for sure whether your copy is effective or not. Everything before that point is just a guess about the problems you think your product solves and all the benefits you think it provides.

Luckily, there are things you can do to inform that guess and make it the best it can be.

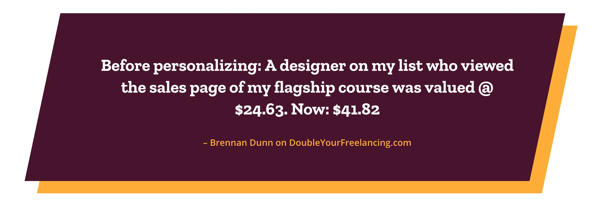

What are those things? Brennan Dunn summed them up well in this tweet:

You know what makes writing sales copy reallllly easy?

20+ hours of talking about your product to 20+ people over the last 2 weeks.

— Brennan Dunn (@brennandunn) August 1, 2017

The product he’s talking about is his new website personalization tool, RightMessage, which he’s been rolling out publicly over the past month or two.

Brennan’s been doing what this software allows users to do (personalizing his website) for years, so when he started making it available to the public he could have just decided he already had all the answers about how and why people would use it.

After all, he already knew how he used it and how it had benefited his business. He even had numbers to prove it.

Instead, he scheduled TONS of demo calls so he could hear about problems directly from those experiencing them. Since then, he’s been iterating new sales page copy based on what he learned.

Of course, when he described what went on in those demos as “talking about your product,” he was abbreviating a bit. I sat in on one of the demos and here’s what I observed:

- More time was spent asking questions and listening than demoing the product

- He listened for specific use cases the customers saw for the product in their businesses

- He listened to how customers might want to use the product (did they want to implement it themselves or have RightMessage’s help implementing it and running experiments?)

- He tried to understand not only how they would use the product, but what problems it would solve, how they thought about those problems, and other ways they’ve tried to solve them

- And yes, there was actual “talking about the product” and showing it in action. Because obviously there’s more to a demo than just getting ideas for great sales copy 🙂

Until you talk to other people about your product, you often end up just writing copy to sell it to yourself.

You also don’t have to stop at just researching your own users. It’s super easy to head over to sites like Quora, Reddit, Amazon, etc. to research how people in your market think about similar products. When you find interesting comments, stow them away in a swipe file for future inspiration.

4. Confront your biases and insecurities.

It’s hard to objectively write about something when you’re so close to it.

Writing about something you’ve built is challenging because it forces you to battle any insecurities or biases you have toward it.

If you’re not confident in your product, it will show.

If you think every feature of your product is god’s gift to the world, it will show.

If you’re more focused on the long-term vision of what you want your product to eventually be, rather than the specific ways it can help people right now, it will show.

You have to separate yourself from the product. Doing so will help you write about it better and make you more receptive to critical feedback.

Ed Catmull touched on this in his excellent book Creativity, Inc. when he described Pixar’s process for editing and refining their works in progress:

“The film—not the filmmaker—is under the microscope. This principle eludes most people, but it is critical: You are not your idea, and if you identify too closely with your ideas, you will take offense when challenged.”

You are not your idea. You are not your product. You are not your customer.

5. Beware copy fatigue.

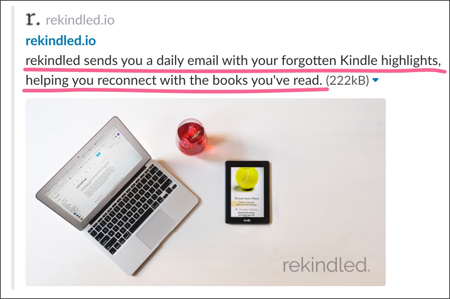

Funny story: I shared a link to the Rekindled page (the one I discussed at the beginning of this post) with a friend on Slack and this came up as the link description:

“rekindled sends you a daily email with your forgotten Kindle highlights, helping you reconnect with the books you’ve read.”

That’s pretty much exactly what I would’ve loved to see on the signup page!

While I don’t know exactly why that wasn’t used on the page itself, I do know from personal experience that there are always a million things to write when launching a new product or feature: emails, social posts, landing page copy, copy that actually goes in/on the product, internal and support documentation, etc.

I call this copy fatigue.

It’s what happens when you have so many chunks of words to deploy in various places that it all starts to run together.

It’s easy to get burned out in the process. Or second guess using a good line of copy in more than one place. Or talk yourself into coming up with something exciting and different for the landing page.

That’s why I recommend always reviewing and reevaluating your copy soon after your initial launch. Preferably in the middle of it. Often, you learn stuff about your customers within hours of liftoff. What you wrote 48 hours ago is already missing the mark. Don’t be afraid to review and tweak on the fly.

What’s Your Process for Writing About Your Own Products?

I’d love to hear how you approach this unique challenge. Are you already keeping any of these rules in mind? What else could I add? Leave a comment and let me know!