There’s been something about the way Apple is promoting its new smart speaker, HomePod, that I can’t quite put my finger on.

Tim Cook set the tone for how they would promote the device back when he introduced it in 2017. He started by reminding everyone how much Apple truly has revolutionized our relationship with music over the years:

“Music has always been a part of Apple’s DNA. We first revolutionized the music industry with iTunes. Then we forever changed the way people listen to music on the go with the iPod. And today, iPhone has become the best portable music player in the world, and it’s even better when it’s paired with Apple Music. You now have 40 million songs in your pocket.”

Cook went on to set up HomePod as a device that will be just as impactful:

“We have such a great portable music experience, but what about our homes? We think we could do a lot to make this experience much better. Just like we did with portable music, we want to reinvent home music.”

What a set up! I remember how incredible that reinvention of portable music was. I remember the magic of “1,000 songs in your pocket.” I remember how great it felt to tune out my dad’s bottomless vault of Moody Blues mix CDs without having to lug my giant CD wallet on family vacations.

My point is, as soon as Cook said Apple was about to reinvent home music in similar fashion, I was here for it.

So why has all of their HomePod marketing and advertising since then felt so…flat?

I get that some products have to be experienced before they wow you, but we can probably agree that Apple’s historically been pretty successful at making you feel the brilliance of their products and brand through advertising.

My first encounter came on the HomePod product page:

It looks like Apple. It sounds like Apple.

But something about it doesn’t feel like Apple (more on that in a bit).

That feeling got worse when my wife and I saw one of their commercials. It’s 12 seconds of the word HomePod distorting and pulsating to the beat of Kendrick Lamar’s “DNA,” followed by three seconds of quick product shots, the words “Order Now,” and the Apple logo:

Before returning her attention to her phone, my wife had a succinct review:

“That commercial sucked.”

I…know? I found myself thinking. I didn’t want to agree! Not only do I like Apple, I like Kendrick Lamar too. I’ve even tweeted about how much I like Kendrick songs in commercials—I should love this!

Look, if there’s anyone who can get away with just throwing a new product’s name in your face for 15 seconds and expecting you to buy it, it’s Apple. They’re not the same company they were in 2001, when they were still fighting back from irrelevance. They can simply say they’re reinventing something and millions of people will eagerly open their wallets.

But every reinvention has a great story, and it sure would seem odd for Apple to miss the opportunity to tell us this one’s.

That’s why I figured I must be missing something. So I did two things:

- Went back and studied how Apple marketed their reinvention of portable music in magical, memorable fashion.

- Compared that to how they’re marketing their reinvention of home music.

In the end, I found several clear differences that can’t simply be explained away by the passing of time and the change in Apple’s market share and brand status.

To understand them, we need to start with a quick review of the first time Apple reinvented music.

Apple and the Reinvention of Portable Music

Apple’s reinvention of portable music began with iTunes and the iPod, but there were two driving forces that pushed them to want to reinvent portable music in the first place.

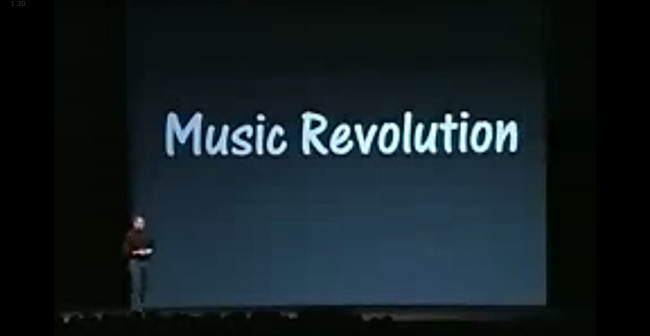

The first was what Steve Jobs described as a music revolution. He framed the entire iTunes announcement at the 2001 Macworld Expo with this idea.

“There is a music revolution happening right now,” he said. “That music revolution is digital music on computers. So for those of you who are not participating in this, let me describe it to you…”

He proceeded to describe how people were using computers to rip audio from CDs onto their hard disks, mix tracks onto their own custom playlists, and burn them onto CDs that they could listen to them anywhere.

“People are doing this like crazy. They’re doing it like crazy!” he said while pointing out that 320 million CD-Rs were sold in the U.S. the previous year (2000).

Next came a quick look at a few of the existing tools that allowed you to take part in this music revolution. And guess what? They objectively sucked!

RealJukebox, Windows Media Player, MusicMatch. These were the popular music “jukebox” applications of the day, and they all had clear shortcomings: overcomplicated, limited audio quality, and slow burning speed (unless you paid for the premium version).

iTunes was introduced as the tool that would finally make participating in the music revolution simple, without sacrificing quality.

“We’re late to this party, and we’re about to do a leapfrog,” Jobs said.

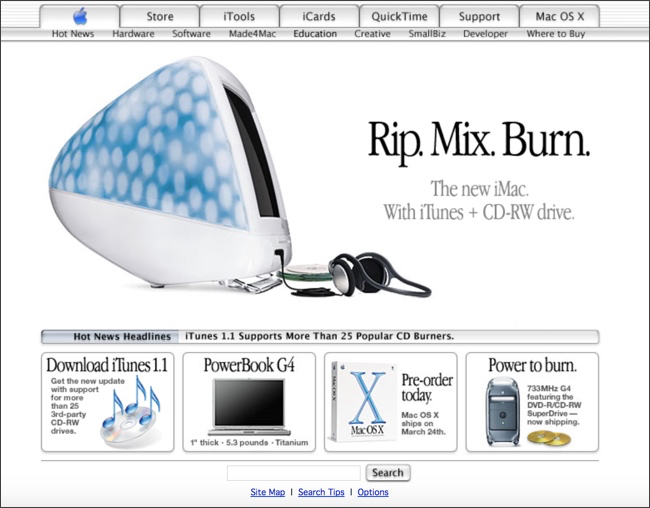

But they didn’t just release a better jukebox. They used iTunes to beat the drum of the music revolution in their marketing:

iTunes and a Mac made joining the revolution easier than ever, and they didn’t have to tell you that. “Rip. Mix. Burn.” made you feel it.

The next step came at the end of 2001, when Apple promised the unveiling of a “breakthrough digital device” they insisted wouldn’t be another Mac.

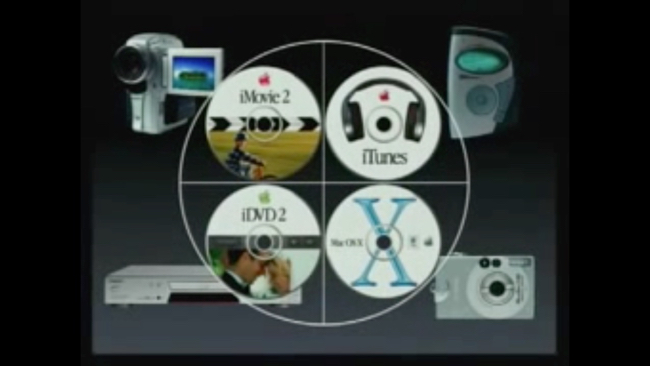

It was the next phase of the digital hub strategy they’d started talking about at the beginning of the year—their plan to make the Mac the “center of your digital lifestyle” by creating powerful software applications that made your digital devices even more valuable.

The goal? To make the Mac “an essential part of your life, where you can’t get along without it,” according to Jobs. iPhoto let you easily transform your digital photos, iMovie let you easily transform your digital videos, and iTunes let you easily transform your digital music.

But while Apple’s software was built with the devices in mind, none of the devices had been built with Apple’s software in mind. What if, Jobs posited, someone built a device that knew everything about Apple’s software, bringing users “a level of integration that no one’s ever achieved before”?

Apple decided to do it. And the device category they chose was music. But why build a music device when they just as easily could have built a video or photo device?

“Well, we love music,” Jobs said. “And it’s always good to do something you love.”

But there was more to it than that:

“More importantly, music’s a part of everyone’s life. Everyone. Music’s been around forever. It will always be around. This is not a speculative market. And because it’s a part of everyone’s life, it’s a very large target market all around the world. It knows no boundaries. But interestingly enough, in this whole new digital music revolution, there is no market leader.”

A revolution without a market leader. That’s not just a recipe for a great product, it’s also a recipe for a great story—one they’d already started telling with “Rip. Mix. Burn.” The iPod was the next chapter, and it represented a massive step forward for music listeners.

“To have your whole music library with you at all times is a quantum leap in listening to music,” Jobs said.

You already know what that became:

Reinvention you could see in a single line of text. There was nothing else like it.

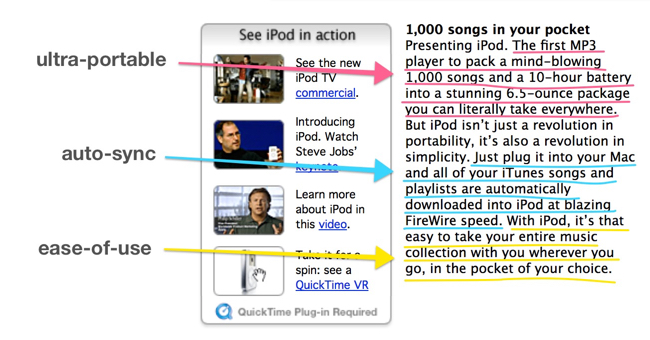

As Jobs said in the presentation, there were three major breakthroughs in iPod that made it such a transformational device:

- Ultra-portable—it was the only MP3 player that could hold 1,000 songs and still fit in your pocket

- Apple’s legendary ease-of-use—the simplified UI and scroll wheel were differences you could see immediately

- Auto-sync—plug it in and all your new songs and playlists automatically sync to your iPod (this might not seem like a big deal now, but it was at the time)

Notice how you could see all three of these things in the first iPod commercial:

And they were all clear in the first paragraph of copy on the product page:

This was what reinventing portable music looked like. Consumers could see three things:

- A stated change they could feel in the market (the “music revolution”), which trickled down into Apple’s marketing

- A memorable value proposition that made benefits and use cases clear (“1,000 songs in your pocket”, “Rip. Mix. Burn.”)

- Transformational features that were showcased in their marketing materials, from commercials to web pages

How many of the elements that created such fantastic marketing messages for the reinvention of portable music are present to sell the reinvention of home music with the HomePod?

Let’s take a look.

HomePod and the Reinvention of Home Music

“This is really exciting.”

Those were the first words from Phil Schiller, Apple’s senior vice president of worldwide marketing, after Tim Cook passed him the mic to continue introducing the HomePod at WWDC 2017.

“The chance to reinvent the way we enjoy music in the home. I can’t think of anything that matters more to so many of us.”

This is when one of the clearest differences between the way Apple positioned its reinvention of portable music versus its reinvention of home music became apparent. Steve Jobs kicked off Apple’s first reinvention with an unforgettable line: “There is a music revolution happening right now.”

That’s part of what made iTunes and iPod so exciting—Apple was joining this wave of change sweeping through music to fix the things that were holding it back. They had a clearly articulated, exciting reason for reinventing portable music, which allowed people to plainly see the limitations of the current listening experience.

But instead of asking, “Why reinvent home music?” Schiller posed a different question, which led to only half an answer:

“Why hasn’t this happened yet? There certainly are a lot of companies hard at work making products to enjoy music in our home, but none of them have quite nailed it yet.”

He then cited two of the most prominent examples of companies that haven’t “quite nailed it yet,” Sonos and Amazon. Sonos speakers sound great, but aren’t smart. The Echo is smart, but doesn’t sound good when you listen to music.

These are certainly good points (although I don’t think “reinventing home music” has ever been Amazon’s goal with the Echo), but he missed the forest to highlight the trees.

Sure, no one’s nailed home music yet, but why is anyone trying to transform our homes with speakers in the first place? Because there’s another revolution taking place: the way we experience our homes is changing dramatically.

I can walk into my bedroom and tell an invisible cloud assistant to turn my lights on. I can tap a button on my phone to adjust the thermostat when I’m not even home. I can get help on a recipe in the kitchen without stopping to wash my hands.

But what have we sacrificed so far in this revolution? Getting to experience the music we love the way it deserves to be experienced.

Placing HomePod in this context is a subtle but important difference. It still differentiates it based on music, but it also implies from the start that it’s going to help you run the rest of your home too (which consumers expect when they see a device that looks remotely like Echo and Google Home).

Imagine instead he’d said something like:

“The experience we have inside our homes has changed more in the last two years than it has in the last decade. We can control our homes with a simple tap on our phone or a spoken request. Our speakers have gotten smaller and become wireless. But with that change, we’ve sacrificed something all of us love—music. Modern speakers aren’t built for this smart home revolution. The ones that sound good aren’t very smart. The ones that are smart don’t sound nearly good enough for us to enjoy our favorite songs the way they were meant to be enjoyed.”

In this alternate way of framing the reinvention of home music, music is something that needs to be saved. It’s something that hasn’t been given the proper attention, that we deserve to experience in a new way.

That feels like the kind of message that could trickle down to much more compelling marketing campaigns than what we’ve seen so far. After all, the revolution Jobs spoke of trickled down into memorable messages like “Rip. Mix. Burn.”

All we’ve gotten this time is “Welcome HomePod.”

Like I said earlier, it would be stupid to analyze any differences between the way Apple is marketing a product in 2018 and the way they marketed a product in 2001 without acknowledging the massive difference in their market position and brand perception between then and now.

When you’re the world’s most valuable company and you have a solid gold brand, a clever, wink-wink headline that basically just tells customers to say hello to your amazing new product can work just fine.

But the stranger part of the headline is the other side of its double meaning. To me, the “Welcome Home” connotation speaks much more to HomePod’s capabilities as a home assistant than its capabilities as a breakthrough music speaker, which is the opposite of how Apple has marketed the device so far.

Unfortunately, the tension between breakthrough music speaker and intelligent home assistant has been there since Schiller’s presentation.

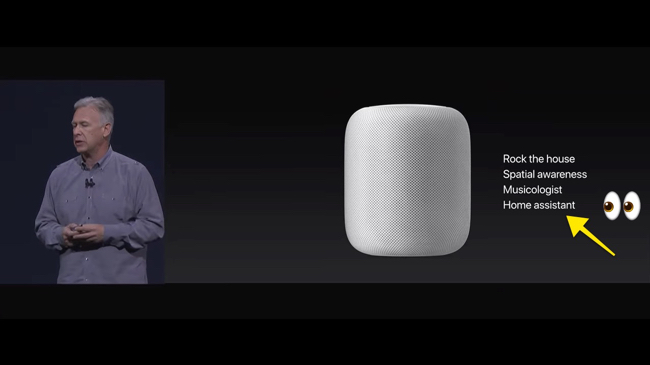

After introducing HomePod as the device Apple has built to reinvent home music, he listed out three things it would need to be great at in order to deliver a “breakthrough experience” (in similar fashion to Jobs listing the iPod’s three “major breakthroughs”):

- It has to rock the house. (Self-explanatory.)

- It needs to be spatially aware. (That basically means it needs to sound great in any kind of room.)

- It has to have a built-in musicologist. (It needs to learn your taste in music and recommend things in a fun, interactive way.)

He spent about five minutes talking about the features that allow HomePod to deliver those three things before summing them up in one-two-three fashion. But then some weird happened—he added a fourth thing:

This might not be so odd if it had been saved as a surprise “but wait, there’s more,” but it wasn’t. Instead, he said the following with noticeably lower enthusiasm:

“And since Siri’s built in there and you can speak to it, the team’s also worked hard to make it a great and helpful home assistant as well.”

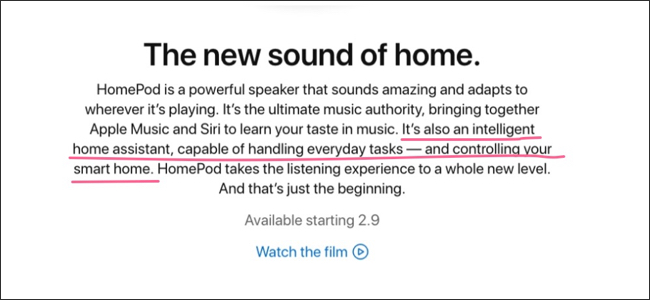

The only way to describe how this feels is tacked-on, which is the last thing we expect from a company that’s built its brand on simplicity. That feeling unfortunately carries over to the product page too. Let’s revisit that opening paragraph, particularly the line about HomePod’s home assistant capabilities:

Notice the superlatives used in the first two sentences—it’s a “powerful speaker that sounds amazing” and the “ultimate music authority.” But when the home assistant features come up, it’s just “capable.” Nothing revolutionary, it just does what all the other smart speakers do.

You can also see they haven’t quite yet found a way to communicate the value of “spatial awareness.” The opening line tells you HomePod “adapts to wherever it’s playing,” which doesn’t feel like a benefit the average consumer can quickly understand.

The home assistant aspect doesn’t come up again until the bottom of the page, and even then they have to reiterate that it’s primarily great at playing music:

And where is this section? Tacked onto the bottom of the page:

It’s not at all a secret that Siri is way behind Alexa and Google as a voice assistant. That’s why it makes sense for Apple to differentiate HomePod on sound quality and position it as the reinvention of home music.

But flawed or not, advertising its home assistant capabilities with an “Oh by the way” only muddles things. They need to find a message that unifies the two so they can tap into the shared smart speaker story consumers have been living.

Nilay Patel, editor-in-chief of The Verge, touched on this in a slightly different way in his review of the HomePod:

“The HomePod, whether Apple likes it or not, is the company’s answer to the wildly popular Amazon Echo and Google Home smart speakers. Apple is very insistent that the $349 HomePod has been in development for the past six years and that it’s entirely focused on sound quality, but it’s entering a market where Amazon is advertising Alexa as a lovable and well-known character during the Super Bowl instead of promoting its actual features. Our shared expectations about smart speakers are beginning to settle in, and outside of engineering labs and controlled listening tests, the HomePod has to measure up.”

He’s talking about the product itself, but I’d say the same is true for their advertising.

What Happens Next?

Apple still might sell a ton of HomePods. They’re not nearly as reliant on creating a compelling marketing campaign as they used to be. They have stores that I’m sure will showcase the device’s incredible sound quality. Based on early reviews, it more than delivers on that front.

Beyond that, they have something now they didn’t have in 2001: ecosystem lock-in. Apple Music is the only music service you can control completely with your voice on HomePod. The others can only be played over AirPlay. And with a subscriber count that, according to WSJ, will soon outnumber Spotify’s, there are more and more people who may want the best speaker for their streaming service.

I like the way Ben Thompson put it in his “Apple’s Middle Age” piece:

1. Customer owns an iPhone

2. Customer subscribes to Apple Music because it is installed by default on their iPhone

3. As an Apple Music subscriber, customer only has one choice in smart speakers: HomePod (and to make the decision to spend more money palatable, Apple pushes sound quality), from which Apple makes a profit

Perfecting the right marketing message may not be necessary for the product’s success, but it could certainly help. And it would definitely feel a lot more like the Apple that reinvented portable music.