Last week, the New York Times reported that Amazon is “quietly eliminating list prices.”

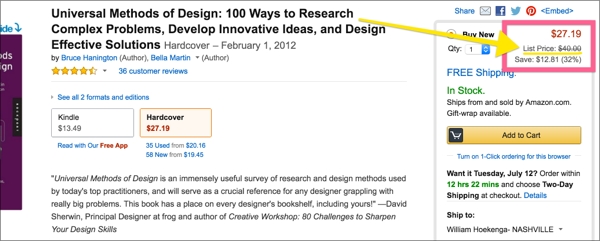

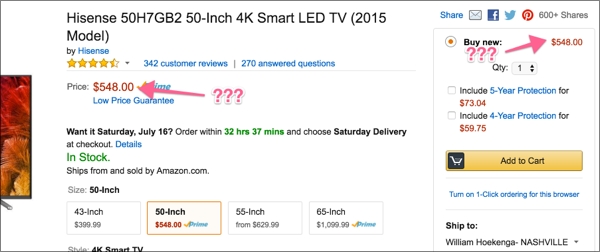

You know, these things:

One analysis showed they’ve been removed from around 70% of Amazon products, up from 29% in May.

Why is this important? Well, those higher list prices are usually listed and crossed out to let you know you’re getting a deal. It’s an effective tactic retailers have been using for decades. And if Amazon, a data-obsessed company that has the traffic and volume to meaningfully test everything they do, is eliminating it, that might mean they’ve discovered something the rest of us don’t know, right?

After all, Amazon has been a trendsetter of digital commerce since the ‘90s, when they patented one-click purchasing.

That’s right—anyone offering customers one-click purchasing should be licensing the technology from Amazon. That’s what Apple had to do to offer the option in iTunes. I’m going to go out on a limb though and say that most of the thousands of tiny online stores who snatched Amazon’s one-click idea aren’t paying any licensing fees.

Pretty much everyone who sells something online—particularly e-commerce—has been looking to Amazon for insight into what’s working for over a decade.

So we should expect the same for list price removal, right? In fact, you and I should immediately remove list price from any products we’re marketing, yes?

Well, before we can answer that, it’s important to ask why Amazon might be doing it in the first place.

Why Is Amazon Killing List Prices?

Two main theories have emerged from outside observers (Amazon itself has been mum, naturally):

Theory #1: Amazon has trained its customers so well, the appearance of a discount is no longer necessary.

The Times brought this up as a possibility in their article (emphasis added):

“When Amazon began 21 years ago, the strategy was to lose on every sale but make it up on volume,” said Larry Compeau, a Clarkson University professor of consumer studies. “It was building for the future, and the future has arrived. Amazon doesn’t have to seduce customers with a deal because they’re going to buy anyway.”

This was the first thought that crossed my mind, and I didn’t have to spend too much time on Twitter to see that others, like behavioral design expert and Hooked author Nir Eyal, had reached the same conclusion:

This makes sense. Amazon’s share of the e-commerce market from January to April 2016 was 41.2%. Best Buy and Nordstrom were in second place with…2.7%. In 2015 alone, Amazon’s e-commerce sales increased by $23 billion.

They have more customers than anyone else. And, more importantly, an increasing number of those customers have every incentive not to go anywhere anytime soon.

As of January 2016, Amazon Prime has an estimated membership of 54 million members in the U.S. That accounts for about 46% of the country’s households.

In return for a $99 fee, Prime members get free 2-day shipping, access to Amazon’s streaming video service, and a bunch of other perks.

What does Amazon get? Lock-in.

Prime members spend an average of $1,100 per year on Amazon (not including their membership fee). That’s $500 more than the average non-member spends in a year.

So it’s fair to say that Amazon’s selection, reviews system, convenience, reputation, and performance may have helped create habits that cannot be swayed by the removal of a tried-and-true conversion optimization technique like list prices.

But to say that without mentioning Theory #2 wouldn’t be telling the whole story.

Theory #2: Amazon fears legal action.

List prices, unfortunately, are often total BS.

Just look at what one Amazon merchant had to say about the list prices in his Amazon store suddenly disappearing (think of merchants as third parties that sell their products through Amazon):

“I’m well aware that it is bogus but it is a common marketing tactic that works very well at boosting sales.”

Whether it’s a cast iron skillet “marked down” to $299.99 from some mystical $500 list price, or yet another 3-video bonus series “valued at” $2,000 that you get for pre-ordering a $12 book, marketers have been abusing consumers with mystical list prices that all too often are pulled out of their asses.

You know it. I know it. That dude with the Amazon store definitely knows it. And now, the legal system knows it.

According to the Times article, retailers like Macy’s, J. Crew, and Ralph Lauren have already been hit with lawsuits thanks to bargains that didn’t really turn out to be bargains. And those are just three of the 24 cases that have already been filed in 2016—which is just one shy of the entire total from 2015.

Back in March, J.C. Penney paid $50 million to settle a class action lawsuit for slapping a bogus list price on some blouses.

They didn’t admit to doing anything wrong…but settled to avoid further legal costs.

Riiiiiiiiiiiiight.

While Amazon hasn’t given any indication they’ve done anything wrong, it’s fair to raise the possibility that legal concerns factored into the decision to remove so many list prices.

A Possible Third Theory

Since 2014, Amazon has experimented with launching its own private label brands.

Much like Target has their own Archer Farms line of products, Amazon now has Amazon Elements (baby wipes is one of their most popular products). And according to the Wall Street Journal, they only have plans to launch more.

This is where things get tricky. List prices are traditionally set for retailers by manufacturers…but what happens when you’re the manufacturer and the retailer?

List prices become pointless.

Instead, you should have just one single price—the one you set when you first listed it for sale. If you decide to promote it at a discount, then you could have that higher price listed as the original price, but to list it from Day 1 with a made-up “list price” would be misleading.

Here’s the point: Amazon’s private label products would be missing the crossed out list prices that show shoppers they’re saving money, but all the products they’re competing against would have them, putting Amazon’s products at a disadvantage.

Eliminating list prices across the board, however, levels the playing field for Amazon’s private label products.

I haven’t seen anyone else suggest this, but if Amazon has a big vision for their private label products, it could be a factor.

So…Should You Still Use List Prices?

It’s impossible to know for sure why Amazon has been removing list prices. I believe the most likely scenario is a combination of all three theories—they’ve ingrained buying habits into a loyal (and extremely large) customer base to the point that price may be less of a priority in their purchasing decisions. And they’d also like to avoid being sued.

These are the things the vast majority of businesses should take away from this:

1. If You’re Going to Use List Prices, Only Use Them When They…You Know…Actually Exist.

The list price is the manufacturer’s suggested price. It’s not some number that every product is automatically given. If you’re selling a downloadable PDF you just created, it does not have a list price. It has the price you sell it for, and that’s it.

2. But Discounts and Sales Are Different.

If you decide to put a product on sale at a discounted price, and you want to list the original price to emphasize the deal, that’s totally fine…as long as you actually sold the product for that original price at some point. The same applies to pre-sales—listing both prices is fine as long as you actually follow through with raising the price in the future.

3. Kill List Prices If You’d Like, But Proceed with Extreme Caution When It Comes to Sales.

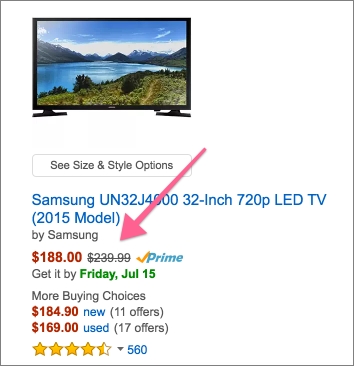

Personally, I’m a little shocked that Amazon is even killing list prices on some items that are legitimately on sale. For instance, check out this TV I found in their deals section:

This is from the search results. As you can see, the original/list price is included.

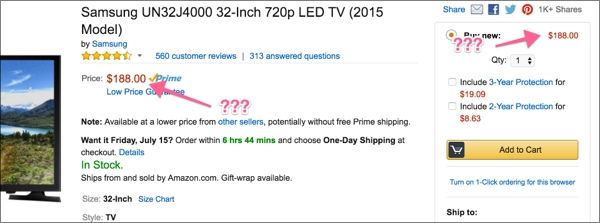

But look what happens on the product page itself:

The price it’s marked down from is gone!

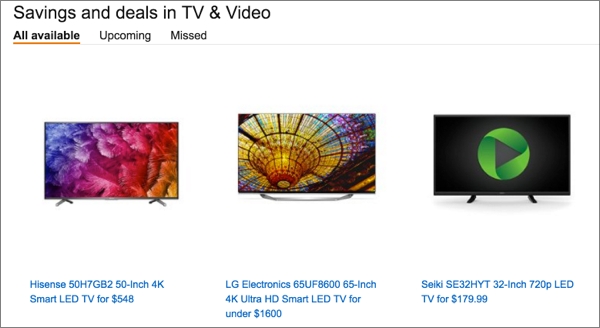

And this, from their “Savings and Deals” section in the TV category, is even weirder:

Apparently, these are deals, but no discount or original price is listed. And the case is the same on all the individual product pages:

Maybe Amazon considers these “deals,” but not “savings” since there is no discount listed. Who knows? But you can also quickly find other deals and savings pages where the list prices and discounts are listed.

Despite what results Amazon may or may not be getting from all this list price removal, I’d recommend leaving it on any legitimate sales or promotions you run. Most people want to compare prices to make sure they’re getting the best deal. The more information you can give them right there on your site to assure them they are getting a great deal, the better. This is one of those best practices that rarely has exceptions.

You have to be the one to decide whether experimenting with removing list pricing is right for your business. The answer will depend on many factors, like brand, market, customer base, etc.

But here’s what I do know: you should not base marketing and pricing decisions solely on what a company like Amazon is doing.

Most likely, Amazon’s business is not like yours. So before you start thinking about how to mirror their tactics, you should take a look at the differences between your businesses, products, and customers.

I made a similar point in “Stop Paying Attention to Split Test Results,” but in a sea full of “How to [Achieve Amazing Result] by Doing What [Massive Famous Company Did]” articles, context is often forgotten.

So, what do you think of Amazon’s list pricing changes? I’m curious to hear what factors you think are influencing their decisions, and whether businesses will begin to follow suit or not. Leave a comment and let me know.